Songs need to build energy in the verse and release it in the chorus. Here’s how.

_____________

Download “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 6-eBook Bundle, and solve your songwriting problems TODAY.

_____________

There is a characteristic of verse melodies that I describe as “begging for the chorus.” All that means is that there appears to be a kind of “pent-up energy” in good verse melodies. Another way to describe this is to say that good verse melodies sound “pleasantly unsettled”, searching out some kind of resolution, a release of musical tension that will eventually happen in the chorus. Good songwriters create these kinds of melodies instinctively, but there is a very easy way for you to ensure that you are creating verse melodies that are begging for the chorus.

There is a characteristic of verse melodies that I describe as “begging for the chorus.” All that means is that there appears to be a kind of “pent-up energy” in good verse melodies. Another way to describe this is to say that good verse melodies sound “pleasantly unsettled”, searching out some kind of resolution, a release of musical tension that will eventually happen in the chorus. Good songwriters create these kinds of melodies instinctively, but there is a very easy way for you to ensure that you are creating verse melodies that are begging for the chorus.

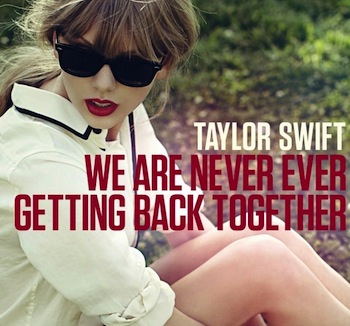

The lead single from Taylor Swift’s new album (Red), “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” (written by Swift, along with Max Martin and Shellback) demonstrates this principle clearly and very effectively. The verse is pleasantly unsettled, and the chorus is exuberant, releasing all of the tension built up in the verse melody.

But how is the verse tension created? And what is it about the chorus melody that so effectively releases all that pent-up energy?

It has to do with the principle note of the verse melody: the dominant note. The dominant note is the 5th note of the key you’re in. This song is in G major, making the dominant note D. Any time you write a melody that sits in and around the dominant note, you build energy.

Listeners instinctively find the dominant note to be a bit musically “insecure” (which is where this energy comes from), but why? To use an analogy, the dominant note sounds like the top point of a pyramid, with the tonic note at the bottom. In that sense, the dominant note sounds like it wants to move, and it does. All through that verse we hear the melody moving off of that dominant note, only to get “thrown back up there” again. This constant moving back to the dominant increases musical energy.

Listeners instinctively find the dominant note to be a bit musically “insecure” (which is where this energy comes from), but why? To use an analogy, the dominant note sounds like the top point of a pyramid, with the tonic note at the bottom. In that sense, the dominant note sounds like it wants to move, and it does. All through that verse we hear the melody moving off of that dominant note, only to get “thrown back up there” again. This constant moving back to the dominant increases musical energy.

And another melodic aspect that builds energy: that dominant note (D) is the principle verse note even when the chords don’t normally include that note. So all through the verse we hear the chords C (C-E-G) and Em (E-G-B), neither of which usually have a dominant note in their structure. Again, musical energy is increased.

That constant building of musical tension is the quality we’re talking about when we describe verse melodies that beg for a chorus.

In the chorus of “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together”, the melodic structure changes. The tonic note (G) now becomes the principle melody note. All musical phrases either start on the tonic, or move away from and quickly back to the tonic. The note set becomes much smaller, with the melody mainly dwelling on the three notes G-A-B. And that tonic note keeps appearing again and again, releasing all of the verse’s energy.

In your own song melodies, if you really want to create verse energy that resolves with climactic energy in the chorus, play around with the following:

- Avoid over-use of the tonic note in verses. Choose a non-tonic note as a melodic focus, and allow the verse melody to keep returning to that note.

- End most musical phrases in the verse with a non-tonic chord and non-tonic note.

- Musical phrases in the chorus should either start or end on the tonic note.

- If verse and chorus chord progressions are different, the chorus progression should usually be shorter.

- Chorus melodies should use a smaller note-set, dwelling mainly on 3 or 4 pitches.

Song energy is a funny concept, because in a way, we usually describe choruses as being more energetic than verses, and they are. So all of this releasing of energy that we experience in choruses is not to say that energy dissipates or dissolves.

What we really mean is that verse energy is built up without being released. The chorus is where we finally get to experience the release of the energy. That tension-release quality is crucial in successful songs.

_________________

Follow Gary on Twitter

PURCHASE and DOWNLOAD the e-books (PDF format) and you’ll learn much, much more about how to write great melodies, chord progressions, and every other aspect of songwriting.

PURCHASE and DOWNLOAD the e-books (PDF format) and you’ll learn much, much more about how to write great melodies, chord progressions, and every other aspect of songwriting.

Hi again thank you for your answer, it clarified things a lot!

I love that song and now that you mention it i see what you mean.

Actually the reason i ask you this is because i have always thought of the dominant to have the exact same role as you mention in this article but i have found a lot of songs since reading this article, especially in pop and dance, where both the verse and the chorus melody circulate around the dominant note, throughout the song. The tonic is present in both the verse and the chorus but as bass. I don’t really understand that. A song that is for example in B minor has a ton of F# in both the verse melody and the chorus melody.

Keep up the good work!

Martin

Hi, loving your blog, have found a lot of interesting tips here! I was wondering something about this article. Is the role of the dominant the same even when the chorus melody pretty much stays away from the tonic, or even starts on the dominant? Or would the role be the same, but just with a weaker sense of pull?

Martin

Hi Martin:

It’s often exactly the way you just said it… staying away from the tonic, but always feeling the sense of pull back. I’ve been trying to think of a song that demonstrates that clearly – If you know Paul Simon’s “You Can Call Me Al”, you’ll notice that in a way, he does the exact opposite of what you frequently find in verses’ and choruses’ use of tonic and dominant. In his verse, he uses the tonic note a lot, where each mini-phrase starts on a note that’s non-tonic, but immediately descends to the tonic. In the chorus, where you’d think you’d find lots of tonic, you don’t. Instead, you hear lots of melodic phrases that move around the dominant note, as if it is searching for the tonic. And it eventually gets there. So in a way, Paul Simon creates more musical energy right within the chorus itself, by creating musical phrases that dwell a lot on the dominant note, eventually moving to the tonic at the end of the chorus.

Thanks for writing, Martin.

-Gary