The progressions that really connect with audiences are the ones that fluctuate between fragile and strong.

____________

Struggling to build an audience base? “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” shows you every aspect of what makes a great song great. Read more..

____________

A few days ago I wrote a post that dealt with differences between verse and chorus progressions. In this post, I want to give you some precise examples of how that all works. If you find that coming up with a set of chord progressions that works feels more like hit-or-miss than anything else, try thinking of your chords this way:

A few days ago I wrote a post that dealt with differences between verse and chorus progressions. In this post, I want to give you some precise examples of how that all works. If you find that coming up with a set of chord progressions that works feels more like hit-or-miss than anything else, try thinking of your chords this way:

THE SONG:

Most songs focus on one chord as the tonic, or “home” chord, and overall, most of the progressions point to that tonic chord as being the most important one, a kind of musical anchor. With that in mind, however, different sections of the song will vary as to how strongly it allows the tonic chord to play that role of anchor. The following examples give you an idea of how this all works, using the key of C major as an example.

VERSE:

Chords keep the tonic chord within its sights, but might wander off a bit, even to the point of treating some other chord as the tonic (like the vi-chord, for example). So you might create chords that only casually point to the tonic, being content to explore the musical neighbourhood around that tonic chord.

Example: vi iii IV I (Am Em F C)

You notice that the vi-chord (Am) acts almost like a tonic at first, making you think that this song is in a minor key, before it settles into C major.

PRE-CHORUS:

Not every song will have a pre-chorus. But the songs that do are usually ones that have a short verse progression. You’ll use this section to build up some musical tension, by moving toward the dominant chord (i.e., the chord built on the 5th note of your key.)

Example: ii I6 IV vi ii I6 IV V (Dm C/E F Am Dm C/E F G)

In this pre-chorus example, you’ll notice that the bass line will move upward from D to G, and that upward movement builds musical tension, a good thing as it leads to the chorus.

CHORUS:

Chorus progressions work best when they simplify, and when they hover around the tonic chord. You’ll find fewer altered chords, fewer ones that are borrowed from other keys, as everything becomes strong and basic.

Example: I IV V I vi IV V I (C F G C Am F G C)

BRIDGE:

A bridge is an opportunity for your chord progression to really move away from the tonic, and take the listener on an interesting journey. Keep in mind that you don’t have long to do this, often just 8 bars. So think of those 8 bars as being a 4-bar journey away from the tonic, and then a 4-bar journey back again.

Example: vi bVII bIII bVI bVII IV vi V (Am Bb Eb Ab Bb F Am G)

As you can see, you get a lot of chords that move away from C major, starting with the bVII (Bb). But by the time you get to the three final chords of the bridge section, C major is firmly restated.

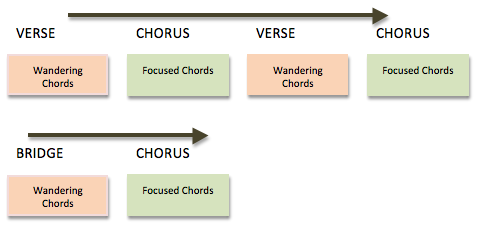

By sticking to this kind of layout, you’ll wind up with a song that fluctuates back and forth between being strongly focused on the tonic, to being less-strongly focused:

That fluctuating back and forth is a critical part of keeping listeners entertained and locked into your musical plan. If you’ve been reading this blog for a while, you’ll know that the “wandering”chord are the type I refer to as fragile, and the “focused” chords are the type I usually call strong.

________

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

________

Thanks Gary. I hope you follow up with a melody post. I always seem to get lost when I try something exotic like the bridge above. What notes should I focus on.

Thanks, Brian. I wrote a post several years ago, called “8 Tips For Writing a Song Bridge,” but I think it’s a good idea to write an article that speaks to the specific design features of the bridge melody. I’ll give that some thought.

Thanks again,

-Gary

Reblogged this on Jerry Rockwell's Dulcimer Blog and commented:

this is one GREAT article! I got a killer 8-chord progression from tweaking one of the chorus progressions….