Most songwriters can tell you what a chord is, and may even be able to tell you that there are 7 chords that naturally occur in any major key. But when it comes to understanding how they work together, and why some chords sound great together while others sound lousy — that’s more of a mystery to them.

Most songwriters can tell you what a chord is, and may even be able to tell you that there are 7 chords that naturally occur in any major key. But when it comes to understanding how they work together, and why some chords sound great together while others sound lousy — that’s more of a mystery to them.

Songwriting formulas are often looked upon negatively by songwriters, but in the case of chord progressions, you’ll find that it’s all about formulas and predictability, in the best sense of those words.

The most effective chord progressions in pop genres are generally the ones that are strongly predictable, with occasional surprises. But why do we speak in terms of chords being predictable? What are they trying to predict?

Tonal music (i.e., music that’s in a key, like all pop songs are) is all about the tonic chord. If your song is in C major, C is the tonic chord. Most of the chord progressions in your song will represent journeys away from and back to the tonic chord. That means you’ll find the following basic progressions will work very well in C major, because they all demonstrate a very concise and simple journey away from, and then back to, the tonic chord:

- C F G7 C

- C F Dm C

- C Am G7 C

- C F Am G C

- C G F G C

Most of the examples in this post will refer to major keys, but the same holds true for minor as well.

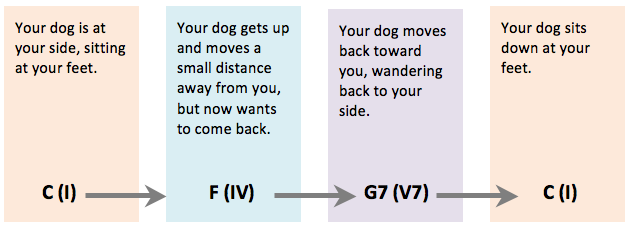

A few posts ago, I used the analogy of a dog’s retractable leash to describe chord progressions. If you’re holding the leash in this analogy, you’re the tonic chord. The leash gets stretched out to some point, and then it slowly (or quickly!) gets pulled back to you. So to take the first progression above and apply the analogy, it would be like this:

In this sense, we’ve created categories of chords, based on the way we typically use those chords. The I-chord (C) represents the feeling of rest and repose, and we call it a tonic function.

The IV-chord (F) represents a journey away from the tonic, and we call it a subdominant function. The V7-chord (G7, though a plain G chord would have worked as well) represents anticipation of the quickly-returning tonic chord, and we call it a dominant function.

But so far, we’ve only described three different chords in the key of C major, and we haven’t talked about the ii, iii, vi or vii chords. How do those fit in to this plan?

There are many ways to categorize chords, and it’s why you can study this topic for years. But let’s take what we’ve learned so far and use it to do to two things that songwriters will find valuable: 1) Chord substitution, and 2) Extending chord progressions. I’m going to deal with extending chord progressions in my next blog post, so for now, let’s look at chord substitution.

Chord Substitution

In general, when different chords have notes in common, there is a good chance that they can sub for each other in a progression. Here’s an example:

- The chord C uses the notes C-E-G.

- The chord Am uses the notes A-C-E.

- The notes C and E are used in both chords.

- Try substituting the C chord with an A minor.

So if you take the progression C F G7 C, it’s worth experimenting with that final C chord, changing it to an Am. You’ll see that in this case, it works quite well:

C F G7 Am

This all takes a bit of theory knowledge, so let’s simplify things to get you going. If we think of simple progressions as being a journey of tonic to subdominant to dominant and back again to tonic, all we need is a list of chords that could act as tonic, could act as subdominant, and so on. Here are those lists:

TONIC: C (I), Am (vi)

SUBDOMINANT: F (IV), Dm (ii)

DOMINANT: G (V), Em (iii), Bdim (vii)

They aren’t comprehensive lists, because there are many things to take into consideration when it comes to substituting chords, not the least of which is considering the melody note. But using those lists, you could rewrite a C-F-G7-C progression to be:

C Dm G7 C

C Dm G Am

C F Em C

C Dm Bdim Am

As you can hear if you play them, each progression is subtly different, conveying differing moods, and that’s what makes them so valuable.

Now, take a look at the progressions you’re using in your current songwriting project. Write them down, categorize them, and then try experimenting with chord substitutions.

In tomorrow’s post, we’ll look at how to take this knowledge and make longer, more interesting and complex progressions that work well in any pop genre.

__________

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 6-eBook Bundle looks at songwriting from every angle, and has been used by thousands of songwriters. How to use chords, write melodies, and craft winning lyrics. (And you’ll receive a FREE copy of “From Amateur to Ace: Writing Songs Like a Pro.“)

Hi Gary,

Great explanation and examples of chord substitution.

I was recently trying to explain it too and found 7th chords can be useful (although that may be more theory than you want to start with here).

So besides saying that Am, Dm and Em are relative minors to C, F and G, we could point out that the Am7, Dm7 and Em7 contain actually contain all three notes of C, F and G. (Just as G7 contains Bdim).

The last one leaves me wondering though – could Em be considered tonic too because it is contained in Cmaj7? Or is it on the fence between tonic and dominant?

What would you say?

Pingback: How to Put Chords Together in a Progression, Part 2 | The Essential Secrets of Songwriting Blog

A Great explanation of (a part of) music theory that most books/ teachers make very confusing. Gary – you’re awesome!

Thanks, Dylan, I appreciate that.

-G