A chord is 3 or more notes all sounding together. Those 3 notes form what we call a triad, and they are the bulk of the chords that get used in most songs written in any of the pop genres (rock, country, folk, etc.)

As you know, there are lots of ways to modify triads. One of the most common ways is to add 7ths. That means that the progression C F G C might become C F G7 C, or C Fmaj7 G7 C, or Cmaj7 Fmaj7 G7 C. If you play through each of those progressions, you’ll notice that the core sound of each progression (including what we call chord function) stays the same. Adding 7ths can change the mood of the progression, or — in the case of G7 — intensify the desire of a chord to move to the tonic chord.

If your songs are sounding like the “same-old same-old”, start reading “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” ebook bundle. You’ll discover the secrets to being creative. Take your music to new levels of excellence!

If your songs are sounding like the “same-old same-old”, start reading “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” ebook bundle. You’ll discover the secrets to being creative. Take your music to new levels of excellence!

One other common way of modifying chords is to invert them. An inverted chord simply means that a note other than the root is at the bottom.

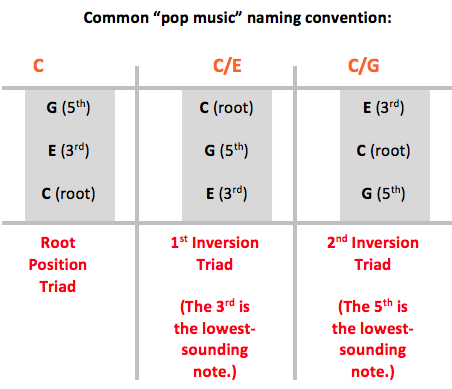

Here’s a chart that lays it all out for you:

Take a moment to study that chart. Along the top row you’ll notice the common way we label chords (C, C/E, and C/G). A letter name by itself (C, for example) means that the root of the chord is at the bottom. If someone tells you to play a C chord, they mean that they want to hear a C-E-G being played together, with the C as the lowest sounding note.

That slash that separates the name of the chord from the bass note is the reason why you’ve often heard of inverted chords as being called “slash chords.”

Root Position Chords

In the first column, you’ll see the standard C chord, with C as the lowest-sounding note. And when you do play that C chord with C as the lowest note, we say that the chord is in root position.

But there are other ways to make chords sound interesting, and that’s where inversions come into play. An inversion means that a note other than the root is going to be the lowest note the audience hears.

First Inversion Chords

So in the second column, you’ll see a chord that has the 3rd (E) in the lowest position. It’s still a C chord, because chords are named for the notes that we find in it. But because E is the lowest-sounding note, it’s going to sound a bit different. Chords with the third in the bottom are called first inversion chords.

LISTEN to a ROOT POSITION TRIAD

LISTEN to a FIRST-INVERSION TRIAD

Second Inversion Chords

In the third column, you’ll see a chord that has the 5th (G) in the lowest position. It’s still a C chord because the chord still contains C-E-G. Chords with the 5th on the bottom are called second inversion chords.

LISTEN to a SECOND-INVERSION TRIAD

When and How to Use Inverted Chords

In most music, there are two main reasons for using an inverted chord:

- to smooth out a jumpy bass line;

- to provide some variety of sound when a chord is held for a long time.

To give you an example of the first circumstance above, play through this progression, strumming each chord for four beats:

C F Bb Eb Dm G C

As you move from one chord to the next, you’ll notice that the bass note will do a fair bit of jumping around. Now play the following progression. Strum each chord in bold print for 2 beats, the others for 4:

C C/E F F/A Bb Bb/D Eb Dm G C

All this is to say that simply throwing inverted chords into your progressions haphazardly is going to sound a bit disjointed and confusing to the listener. The inversions shown above target the two main reasons for using inversions. They smooth out the bass and they provide a nice sense of variety.

All this is to say that simply throwing inverted chords into your progressions haphazardly is going to sound a bit disjointed and confusing to the listener. The inversions shown above target the two main reasons for using inversions. They smooth out the bass and they provide a nice sense of variety.

Inverted chords is one more thing you can experiment with when you work to get your song sounding its best. Remember that inverted chords have a tendency to make a progression sound a bit unstable if you use too many in a row. So injecting them here and there, once in a while, is the best way to use them.

Some Examples

Here are some standard progressions for you to try that use inversions:

- C C/E F G C

- C G/B Am Am7/G F G C

- C F/A F Dm Gsus4 G C

- C G/D C/E F C/G G C

- C G F/A F Dm Dm/F G G7 C

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” eBook Bundle packages. GET TODAY’S BUNDLE DEAL