One of the most important principles of songwriting (and in fact, the most important part of musical composition whether writing songs or symphonies) is the notion that all elements of a song partner well together. In other words, the melodies, lyrics and chords all support each other, and all work together to reveal and enhance the meaning of the song.

That sense of partnership also extends to the various sections within a song. The verse and chorus should operate as partners in the sense that a chorus should sound like the obvious result of whatever the verse is. How to do that may be tricky, but that is what songwriting is all about.

The bridge of a song is optional; many songs become huge hits without that section even existing. When you use a bridge, it’s typically for one or more of the following reasons:

- The lyric isn’t finished after the second go-through of the chorus.

- The song needs a bit of variety, especially when the verse and chorus have a similar melodic structure, or a similar chord progression.

- The song needs a bit more length.

- The song doesn’t have a chorus. (In other words, it would otherwise be a verse-only, or use a verse-refrain form).

And even with those considerations, a bridge isn’t absolutely necessary. But if you do choose to use a bridge, your instincts will tell you that you should take the song in a new direction. Most of the time your instincts will be correct.

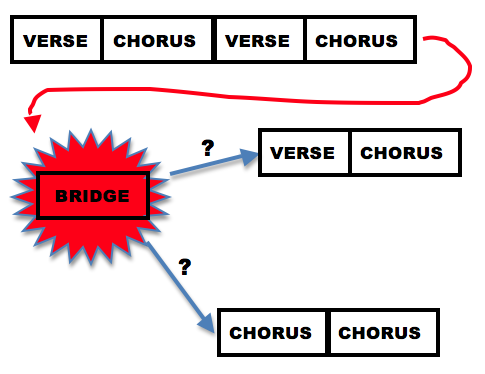

But since bridges are usually only 8 bars or so, it’s not like you have a lot of time to go in that new direction. Once you’re moving away from the themes and harmonies that have defined your song up to that point, it’s time to move back so that you can return to the chorus (or less commonly to a 3rd verse).

If you’re wondering what you can do to make your bridge stand out and extend your song, while at the same time not sound too different from what’s been offered by your verse and chorus, consider these ideas:

- For a song with a major-key chorus, start the bridge on the relative minor. Major and minor keys that are considered to be “relative” to each other are ones that use the same key signature. If you’re a bit rusty on that, here’s a list of major keys and their relative minors. So if your chorus is in E major, try starting your bridge on a C#m chord and go from there.

- For a song with a minor-key chorus, explore the possibilities of the relative major. You’ll find more cases of songs staying in minor for a bridge if the chorus is also in a minor key. That seems to be more prevalent than moving clearly into major. In Katy Perry’s “Part of Me” (Katy Perry, Lukasz Gottwald, Max Martin, Bonnie McKee), though, you’ll notice that the song stays more or less in the same key as the chorus – D minor – but you’ll also notice more F moving to C as chord choices in the bridge, and that’s enough to give the bridge a feeling of having moved into F major. But it’s subtle.

- Change the intensity of the arrangement-production. If your song, particularly the chorus, is high energy, use the bridge to make the instrumentation/production more sparse, and then build it as the bridge comes to a close. You can also use your bridge to build energy throughout, and that works well for songs where you want the final chorus repeats to be the most musically intense moments.

- Create a more adventurous melody. Bridge melodies have a more wandering quality, requiring the singer to move up and down and explore a fuller range than you’d find with a chorus. The creative nature of a bridge melody is going to possibly require you to…

- …Create a more adventurous chord progression. How creative you get with this has a lot to do with the nature of the song itself, as well as the characteristics of your writing style. In general, the bridge is where you’re going to experiment with more altered chords (modal mixtures, secondary dominants, etc.), and chords that have roots that don’t exist in your song’s key (Flat-VII, Flat-III, etc.) Remember that as you get closer to the end of your bridge, you need to pull things back to the key of whatever section you’re returning to — the chorus or the verse.

Always remember that with a “creative” bridge, that sense of creativity needs to be carefully controlled. There’s a danger that a bridge will sound too different, and that’s not usually what the bridge is for. Though changing tempo is possible (Lionel Ritchie’s “Say You, Say Me“, for example), you should think of a bridge as a way to look in a new direction before pulling things back to the song’s verse or chorus.

I’ve recently completed a video that describes these and other ideas related to why you might include a bridge in your song:

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” eBook bundle packages have been helping thousands of songwriters improve their writing technique for the past decade. The Bundle is always offered with a free deal. To see what today’s deal is, visit the online store.

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” eBook bundle packages have been helping thousands of songwriters improve their writing technique for the past decade. The Bundle is always offered with a free deal. To see what today’s deal is, visit the online store.

This article was helpful but I need more. I am currently working on a song in E major and am struggling with the bridge. My co-writer wants to begin the bridge with A, F#m, G#m, and C#m. That being the first line. But she plays keyboard. I play guitar and this structure makes my vocals sound weird. The chorus begins in A. Advice?