It’s a common technique for songwriters to write a verse that sits mainly in a minor key, and then switch to a major key for the chorus. The main reason for this kind of minor-to-major relationship working so well is that it considerably brightens the sound of a song. If you think of the verse and chorus as being the main unit in a song, you start dark and end bright, and there’s something very pleasant about that.

But there’s something else you can try, which is to inject a major key moment into a minor key verse. Sometimes all that needs to happen is to feature the relative major tonic chord briefly, and the song “California Dreamin'” (John Phillips, Michelle Phillips) is a good example of what I mean.

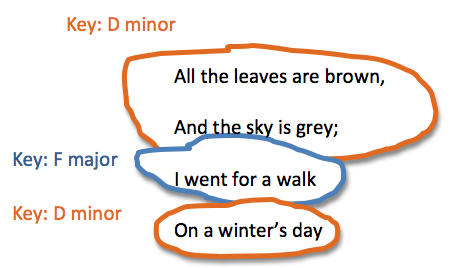

The studio version of this song puts the verse in D minor (actually a rather flat D). For songs in a minor key, moving to the major usually means changing to the relative major, which in this case would be F major.

The first line of the verse gives us these chords:

(N/C) Dm C Bb C Asus A

All the leaves are brown And the sky is grey

The next part of the progression moves distinctly toward the relative major:

Bb F A Dm Bb Asus A..... (Dm)

I went for a walk on a winter's day;

As you can see, it doesn’t take much. Just the Bb and F chords that start the second line give enough of a hint of F major that it feels that the song has, ever so briefly, changed key to the relative major.

And then right away, they follow that Bb-F pair with A moving to Dm, which pulls the music immediately back into D minor.

As you can see, the hint of F major is extremely slight: it lasts for two chords before being brought back to D minor. But it’s enough to create a temporary brightening of the mood, giving the verse a brief moment of harmonic contrast.

It should be noted here that the 4th line of the verse pulls back into D minor due to the Asus-A chords; the D minor chord isn’t necessary to establish D minor as the key.

“California Dreamin’ doesn’t use a chorus, being in a verse-verse-instrumental-verse format. If your song does use a chorus, you can still use this idea of the brief visitation to major in your verse, and then a complete switch to major for the chorus.

In your own minor key song, you can easily move into major by doing the following:

- Identify the relative major of your chosen minor key. If you don’t know how to identify the relative major, check out this graphic.

- Begin your verse in a minor key.

- Find a spot to change key. It often works best to have this happen near the midpoint. To make the change, try using the IV-I chord relationship (as “California Dreamin'” does) or V-I.

- Once you’ve changed to major, immediately look for a way to get back to minor. You can do this by doing iv-i or V-i in the minor.

As I mentioned, the benefit to inserting a very brief visit to the relative major in the middle of your verse is that it offers a bit of contrast to your music, giving a very short moment of brightness.

That kind of variety has a long historical tradition, a technique used even by classical composers who would start a symphony in a minor key, and then move briefly to major.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

“How to Harmonize a Melody” is part of the 10-eBook Deluxe Bundle, written by Gary Ewer. If you can “hear” the chords you want, but you just can’t find them, this ebook will take you step-by-step through a process that works.

Right now the Deluxe Bundle is on sale. Read more..

Pingback: November – Final Track – California Dreamin’ – monthsbymusic

Pingback: Major Key Brightness in a Minor Key Verse - The Hit Songwriting Formula | The Hit Songwriting Formula

Hi.I. really need some clarification on this subject. If it’s not a bother, I would like you to explain using James Blunt’s Give-me-some-love since it’s similar to the example. And also the Fur Elise. Does it change the key when it goes ‘bright’ on the C-G progression and does it change back to A minor on the proceeding Am-E?

Sorry. I’m learning the piano. I’m not a songwriter, at least not yet. But I find your lessons very helpful.

Hi Michael:

“Give Me Some Love” is not really a good example of what I’m talking about in this article. That song’s verse is mainly in a minor key, and the brightness doesn’t happen until the chorus, which is relatively common. I was talking about minor verses that briefly abandon the minor sound and move toward the major for a bar or so.

“Für Elise” is a better example, even though not in a verse/chorus format. The first phrase (minor key) repeats, and the start of the second section moves briefly toward the relative major, just for 1 bar, before settling back into minor.

-Gary

Oh! Ok. I get it now. Thanks a lot.