If you are a fan of the music of J.S. Bach, you might know that he often took the shape of a small melodic fragment, and then planned for the entire piece of music to also adopt that shape.

Here’s how that might work. If you listen to the beginning of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, you’ll notice that it starts with a very short, quick musical idea that runs upward and then downward. You’ll also hear it being passed around to different instruments:

Stop floundering! It’s time to get your songwriting back on track. “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” eBook Bundle packages will show you how to polish your songwriting technique. The 10-eBook Deluxe Bundle comes with a special deal.

Stop floundering! It’s time to get your songwriting back on track. “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” eBook Bundle packages will show you how to polish your songwriting technique. The 10-eBook Deluxe Bundle comes with a special deal.

If you continue listening beyond that point, you’ll notice that the music for the entire first section of the movement generally moves upward, then moving downward again:

In other words, that short little fragment, which has an up-and-down shape, is a kind of “musical premonition” for what happens in the entire first section of that movement:

Bach did this purely as an architectural feature. He felt that it was something listeners wouldn’t consciously notice, but that it would nonetheless strengthen the structure of his music.

How This Might Pertain to Modern Songwriting

You might wonder why we’re talking about Bach on a songwriting blog, but be patient… I think this will be useful for you. There is a way for modern songwriters to take a first musical idea that happens in a song, and then have it pertain to the larger song form.

There are lots of ways to do this. You could do it with regard to melody, as Bach has done, and I wrote a post a number of years ago to show how British songwriter Imogen Heap did something similar in her song “Tidal”, from her 2008 “Ellipse” album.

For today, let’s look at how you might take a short chord progression, and have that progression describe the progressions work for the entire song. Let’s say you came up with a verse progression like this:

C F Dm G |C F Dm G |Am Em Am Em |F G Dm G

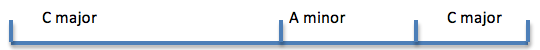

As you can see, the verse would start solidly in C major. By the time it gets to its centre point, the tonality has shifted to Am minor. But by the end, it’s moved back to C major. So the verse progression does this:

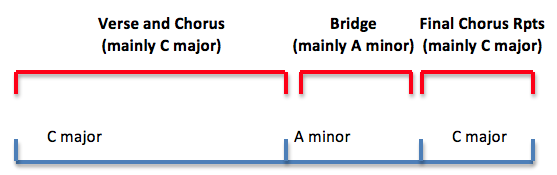

Now, switch your thinking to encompass the entire song. Make a plan to write a song where the verse and chorus are mainly in C major, the bridge is in A minor with a switch back to C major for the final chorus repeats. So even though the verse makes that brief visitation to A minor, we can consider that, generally speaking, it still feels mostly like C major. So the progressions (and the keys you visit) for the entire song do this:

In this way, the verse is like a mini version of the entire song, at least with regard to the chord progressions and the keys you might visit throughout the song.

Other Ways to Replicate Original Ideas

There are many ways you can do what Bach did, and replicate an original idea. Besides doing it with melody and chords, you can also try:

- Song Intros. Let your songs instrumental treatment in the intro replicate what you plan to do for the entire song. If, for example, you’d like for the song to gradually build instrumentation, you could use an intro that starts small and then gradually builds, before dropping back to start verse 1.

- Lyrics. Let’s say that you want your song lyrics to describe a good relationship that’s gone bad, but that in the end, you’re going to be all right. Find a way, early in your verse lyrics, to describe that basic concept of good to bad to good, in a line or two. The emotional up-and-down that that produces can serve as a template for the up-and-down the listener will experience for the entire song.

- Dynamics. If your song goes, generally speaking, from soft to loud, you can have your verse doing that very thing. Then for verse 2, it drops back softer, but louder than verse 1. Each chorus will e louder than the previous one. If you have a bridge, allow that to be even louder… you get the picture. The plan for the verse will be a musical premonition for what eventually happens in the entire song.

What does this kind of technique do for a song? It strengthens its structure. It gives your song a kind of “musical logic”, such that each section behaves in a way that feels natural. Composers have been doing it for centuries, and your own songs can benefit from it.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

Looking for some quick fixes to some of songwriting’s most common problems? “Fix Your Songwriting Problems – NOW” describes 7 stumbling blocks you’re possibly dealing with right now! It’s part of “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle. Get this deal: a FREE COPY of “Creative Chord Progressions.”

Looking for some quick fixes to some of songwriting’s most common problems? “Fix Your Songwriting Problems – NOW” describes 7 stumbling blocks you’re possibly dealing with right now! It’s part of “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle. Get this deal: a FREE COPY of “Creative Chord Progressions.”