This is something that doesn’t necessarily occur to casual listeners to pop music: the number of times we hear a melody that’s really just the same short 4- or 5-note cell that gets repeated over and over with different chords underneath.

Like starting the songwriting process by working out the chords first? There are benefits and dangers. Read “Writing a Song From a Chord Progression” to get this process working properly for you.

Like starting the songwriting process by working out the chords first? There are benefits and dangers. Read “Writing a Song From a Chord Progression” to get this process working properly for you.

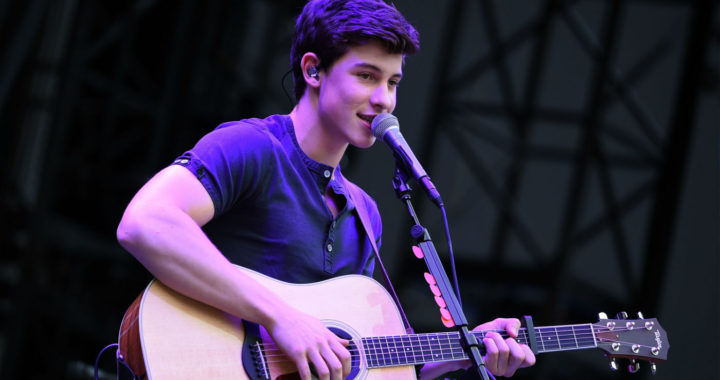

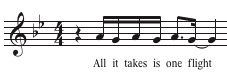

A good example of this is Shawn Mendes’ recent single “Lost In Japan” (Shawn Mendes, Scott Harris, Nate Mercereau, Teddy Geiger), using a verse melody that takes a short 6-note motif that moves up and down on the notes A and G:

With those two pitches, A and G, he creates almost the entire verse, with just a few extra notes thrown in. Give it a listen to see what I mean:

As I say, constantly repeating melodic cells won’t usually be obvious to the casual listener of music. It’s amazing, though, how much of a typical pop song is created using the same melodic motif or shape, over and over again.

So why don’t we usually notice this sort of thing? Generally it’s because other things are changing — the lyric, the chords underneath, and sometimes the instrumentation/production.

In “Lost in Japan”, the lyrics keep changing, but I think the fact that the A-to-G melodic cell is accompanied by four different chords is the reason it slips under the radar. We first hear it accompanied by Bb, then Cm7, then Gm, then Eb.

For each of those chords, we hear the same melodic idea, but with each change of the chord it’s like we’re hearing it “from a different angle”, so to speak.

Why This Is Important

One of the most important benefits of creating entire melodies by stringing together similar cells is memorability. It’s a lot easier to remember a melody that contains the same short segment constantly repeated.

The changing chords and lyrics helps to disguise the constant repetition. So you get the benefit that comes from repeating something over and over (it’s easier for the audience to sing/hum it) while making it sound as though an entire verse has been created out of fresh material.

This is only one melody-writing technique, of course, and there’s nothing wrong with writing a melody where everything changes as it goes (“Hey Jude”, for example).

But if you find yourself struggling to write a melody that’s just not happening, try the technique used in “Lost in Japan”: create a short melodic cell, then sing it over and over, changing the chords underneath.

As long as the chords work with your short melodic idea, your final, complete melody should work as well.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook bundle includes several chord progression eBooks, including “Chord Progression Formulas” and the all-important Study Guide. Learn how to create chord progressions within seconds using these formulas.