Form is one of those words that can cause songwriters’ eyes to glaze over. It sounds like a term that’s only going to help other people understand what you’ve written, but not help the songwriter so much.

Got a melody but don’t know how to add chords to make it come alive? “How to Harmonize a Melody” (high quality PDF) does just that. It shows, step-by-step, how to choose chords that fit your tune, and how to experiment with chord substitutions. It’s part of “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle.

Got a melody but don’t know how to add chords to make it come alive? “How to Harmonize a Melody” (high quality PDF) does just that. It shows, step-by-step, how to choose chords that fit your tune, and how to experiment with chord substitutions. It’s part of “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle.

So let’s look at form from a different angle and then see how much an understanding of song form can be of help to a songwriter.

Here are some basic statements about songs and songwriting that pertain in some way to form:

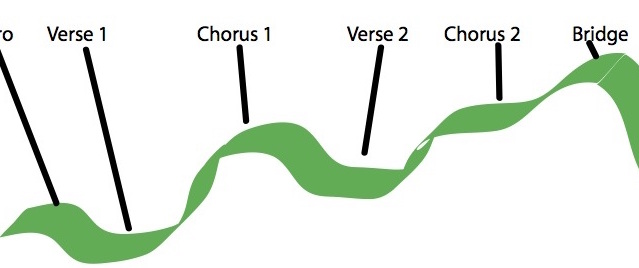

- Most songs are divided up into smaller recurring sections (verse, chorus, etc.).

- Most songs make good use of repeating elements (chord progressions, melodic cells, certain lyrics, etc.).

- Most songs use lyrics that rhyme.

- Most songs have an instrumental plan that involves thinking about when to use a full band, when to cut it back to something more transparent, and so on.

In other words, song form usually means identifying the boundaries of various sections within a song. Sometimes those are larger sections (macro forms, you might say), like when you move from a verse to a chorus.

But form can pertain to things within a section – micro form. For example, you might start your verse with a melody line that moves upward, and then follow that immediately with a line that moves downward. That’s something that contributes to form.

But even all of this doesn’t necessarily mean that form is something relevant to the act of songwriting. Is there a way of considering form that makes it useful to the actual writing of a song?

Using Form to Guide Your Songwriting

It’s perfect if formal considerations happen naturally, without having to even think about them. But here are some formal considerations that you may want to think about as you write your next song:

- Think about the length of your verse and the length of your chorus. Choruses are rarely longer than verses (not considering chorus repetitions), so keep your choruses short and concise.

- Think about the repetition of melodic ideas within any one melody.

- Think about your rhyming scheme. If one verse uses a particular rhyming scheme where every pair of lines rhymes, you’ll usually want to preserve that idea for all verses.

- Think about major versus minor in your chord progressions. If Verse 1 is in minor, and then switches to major for the chorus, let Verse 2 also be in minor.

- Think about ways to allow song energy to gradually build throughout the song. If energy dissipates during the bridge in a way you don’t want, use instrumentation and melodic range (e.g., move the melody higher) to try to build up energy.

There are so many other ways in which the act of songwriting is actually a working out of some detail pertaining to form. In my eBook “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting”, I’ve said:

Bad form is the reason for most of the bad music out there. If you think your music is bad, or at least needs some serious improvement, you may need to look no further than its basic structure.

When songs exhibit good form, it means that there is a sense of consistency from beginning to end. That means that no matter how many changes a song goes through, there is a sense of continuity and connection in play. That continuity and connection makes it easier to see the entire song as one concise artistic statement.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow on Twitter.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow on Twitter.

Thousands of songwriters have been using “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle, along with the Study Guide, to polish their songwriting skills and raise their level of excellence.

Thousands of songwriters have been using “The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook Bundle, along with the Study Guide, to polish their songwriting skills and raise their level of excellence.