Contrast is a big part of what makes great songs great. Even if that contrast is something as simple as loud versus soft (instrumentation) or low versus high (melodies), contrast is crucial to keeping audiences interested.

Within chord progressions, contrast usually happens when differentiating between major and minor. Songs might feature a minor verse, and then switch to a chorus that’s in the relative major key, like Carole King’s classic hit “You’ve Got a Friend”, the verse for which is in F minor, then switching to Ab major for the chorus.

Your songs just aren’t attracting attention? Can’t find the reason? “Fix Your Songwriting Problems – NOW!” describes seven of the most common songwriting problems, along with solutions you can try.

Your songs just aren’t attracting attention? Can’t find the reason? “Fix Your Songwriting Problems – NOW!” describes seven of the most common songwriting problems, along with solutions you can try.

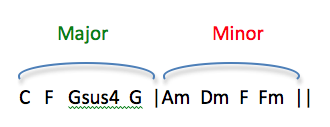

There is another way to contrast major and minor, and that is to do it within the same progression. In other words, you might start a progression solidly in major and then make a switch part way through so that the focus turns to minor. Here’s an example of an 8-chord progression which switches from mainly major to mainly minor:

A few of things to notice. First, the minor side of the progression uses a major chord (F), so being in minor doesn’t mean that all the chords you use must be minor chords. Similarly, even though this progression’s major side uses no minor chords, you can still throw in a minor chord and have the major section still sounding major.

Second, it’s good to check out how the end of the progression moves back to the beginning. You’ll see that it ends on Fm, which does transition nicely back to C.

Third, all eight of the chords come from the key of C major. It’s just that the first four use the major chords from that key, and most of the last four use the minor chords from that key. But I encourage you to experiment. You can reverse this idea and switch from minor to major, and you can also throw in chords that don’t usually belong to the key you’ve chosen.

Here are some more examples you can play around with. They should work in either a verse or a chorus. You can use them easily in a song’s bridge, particularly if the first chord of the bridge is in the opposite mode of the chorus. So, for example, if your chorus is in C major, you could start your bridge in A minor. (In fact, the example above works just as well by playing chords five to eight, then follow it with one to four).

Some of them start minor, others start major, but it’s always best to experiment, change things to suit your song and your tastes. You can play the first half of each progression twice or even more before moving on to the second half.

MORE EXAMPLES:

- Dm Em C Dm |F C Bb C

- Em Bm Am D | G C G D

- C G Am F |Am Dm Em Am

- C G C/E F |Dm Am Dm Em

- G7 C Bb F | Am Em Eb Dm

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

Written by Gary Ewer. Follow Gary on Twitter.

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook bundle includes several chord progression eBooks, including “Chord Progression Formulas”. Learn how to create chord progressions within seconds using these formulas.

“The Essential Secrets of Songwriting” 10-eBook bundle includes several chord progression eBooks, including “Chord Progression Formulas”. Learn how to create chord progressions within seconds using these formulas.